07-01-2020

07-01-2020

Punctured cover: India's crop insurance scheme loses sheen

Insurance Alertss

Insurance AlertssPunctured cover: India's crop insurance scheme loses sheen

Three years and seven crop seasons after it was rolled out, nobody seems to be happy with the Centre's flagship farm insurance scheme, Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana. While the number of farmers enrolling under the scheme has gone down, insurance companies too are pulling out of it.

Ahead of the 2019-20 crop season, three private companies - ICICI Lombard, Tata AIG and Cholamandalam MS - did not bid for the rabi (mid-November to May) and kharif (June to October) seasons due to heavy losses in the 2018 kharif season. This is a worrying trend as the scheme, rolled out during the 2016 kharif season, is largely spearheaded by private players. It started with 10 private insurance companies and just one public insurance company.

During rabi 2016-17, five more companies were empanelled, four of which were government-run. This was the season private player Shriram General Insurance exited from the scheme due to losses. In kharif 2017, two additional private companies joined the scheme taking the total list of empanelled companies to 17. Now, the scheme is left with 14 companies, nine of which are private-run.

While the companies are tight lipped over the reasons for the exit, data clearly tell the story. Profit of an insurance company depends on the claim ratio - the percentage of amount paid as claims in relation to the premium earned. ICICI Lombard and Cholamandalam had made some profits in the first year of the scheme as their claim ratio was 79 per cent and 61 per cent respectively; but they made heavy losses thereafter. Tata AIG made losses in all the three years with over 100 per cent claim ratio.

In fact, most of the insurance companies incurred losses in 2018 kharif season, with nine states - which include Haryana and Maharashtra - recording over 100 per cent claim ratios. In another four states, claim ratios were lower than 100 per cent but higher than the India average of 76 per cent, according to the Union Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers' Welfare.

In Goa, which had the highest claim ratio, insurance companies had to pay out Rs 2.8 for every rupee they collected as premium. In Haryana, it was Rs 1.4. The assessment of rabi 2018-19 is still underway, but companies say a large number of claims have already been filed.

There are two distinct reasons behind the high claim ratio: Surge in extreme weather events and alleged political interference in crop loss estimation.

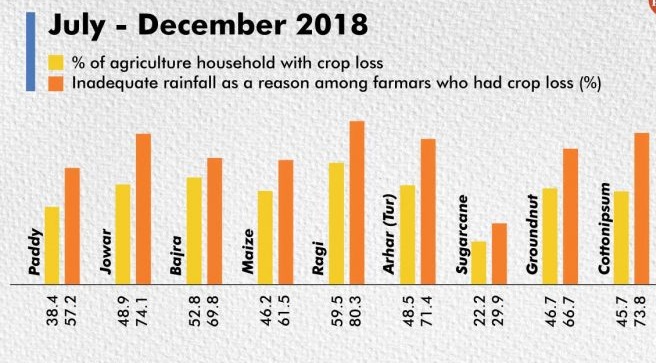

The data of 2016-17, updated till December 2017, shows extreme weather events affected 2.6 million hectares of cropped area in the country. In 2017-18, updated till December 2018, the share nearly doubled to 4.7 million hectares, suggests EnviStats India 2019, released by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

Rajeev Chaudhary, chairperson and managing director of government-run Agriculture Insurance Company Ltd (AICL), says traditionally insurance companies would incur losses during the rabi season, which is associated with freak weather events, and earn profits during the kharif season. "So, we would make a profit of 10-15 per cent every year. This is no longer true," says he.

What adds to the companies' losses is the fact that the scheme covers farmers in the pre-sowing as well as the post-harvest periods, unlike traditional insurance schemes that cover just standing crops. "Most farmers now apply for post-harvest losses, and no insurance company has the infrastructure to verify them," says Chaudhary. He estimates the claims in 2019 kharif season will be the highest ever due to prolonged rainfall in Maharashtra, Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh that damaged key crops such as pulses and cotton.

A senior AICL officer, on conditions of anonymity, says in Maharashtra more than 2.5 million farmers had already applied for 100 per cent insurance money till the first week of November. "The insurance companies in the state will go bankrupt if they honour all the claims," he adds. Most insurance agents Down to Earth spoke to also allege that local politicians and state governments inflate the loss estimation under the crop cutting experiment, which is carried out to ascertain the extent of crop damage.

"In a way, private insurance companies are pitted against state governments who are blindly approving claims without site visits and then asking us to pay up," says a private insurance agent in Gujarat. Media reports suggest that the Rajasthan government asked Tata AIG to pay 100 per cent insurance money to farmers in Barmer district for damages to groundnut crops in 2018 kharif season, even when the company claimed that groundnut was not even sown in the area. "Because of the political influence, farmers do not cooperate with us," says the private insurance agent. Even Chaudhary admits that the crop cutting experiment is not in favour of the insurance companies. He suggests the scheme should have the provision of hiring independent agencies that both government and insurance companies have faith in to carry out the crop cutting experiments.

The economic slump and its impact on the reinsurance market have also marred the scheme. "The commission that insurance companies receive when they reinsure the risk cover has gone down from 10 per cent to just 3 per cent in the past five years. The commission amount itself runs into crores of rupees and this dip has impacted the companies," says an insurance market expert on anonymity. Company officials say their risk has also increased because the number of farmers covered under the scheme has not increased over the years. In 2016-17, more than 58 million farmers were covered under the scheme, which dropped to around 56 million in 2018-19. This has pushed the scheme's premium, which is shared by farmers, the Centre and states. A farmer in 2016-17 paid on an average premium of Rs 725 under the scheme, which increased to Rs 860 in 2018.

The losing interest of private players can seriously weaken the scheme. For starters, it will increase the risk burden of the government companies. Already, the five government-run companies under the scheme cover over 50 per cent of the disaster-prone areas. This is the reason the overall claim ratio of the government companies in the past three years have been substantially higher (86 per cent) than the private players (77 per cent). The remaining players are also expected to increase the premium amount to compensate for the higher risk. This will make farmers more unsure of the scheme.

Chaudhary believes the only way this logjam can be broken is if the Centre intervenes and increases the number of farmers under the scheme and ensures that it covers the entire country. "Currently, only 25 per cent of districts contribute the bulk of the premium. If the farmer base spreads to new places, companies can earn enough to remain in the scheme," he says.

This was first published in Down To Earth's print edition (dated 1-15 December, 2019) We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator's approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the 'Letters' section of the Down To Earth print edition.

Source: Down to Earth