Like the rest of the insurance industry, General Insurance Corporation of India, or GIC Re, had a difficult FY21. At the worst of the trough in the first quarter of FY21, the solvency ratio, a key indicator showing how far assets cover commitments to future payments, went down to 1.52 in June 2020, just above the insurance regulator’s mandated 1.5. That is not the primary problem with GIC Re. As the wicket-keeper for the Indian insurance companies, the larger industry still seems to be comfortable to see India’s sole reinsurer play with a net behind it.

The net is the Government of India’s ownership of the company at 85.78 per cent. It keeps GIC Re from growing up. Even more unfortunately, this structural problem also keeps the Indian insurance business from growing up. It is difficult to judge whether the non-life insurance companies are comfortable not taking on too much risk because GIC Re has a limited capacity to reinsure them or whether it is the lack of adventure among them to pick up business from the large percentage of uninsured, which keeps the company relatively puny by global standards.

GIC Re just makes the cut as the tenth largest reinsurer globally depending on whether one measures the rank by the net premium written or gross premium written (the latter is more appropriate, in which case the company falls out of the league). The ranking is illusory since by size of business, GIC Re is half the size of China Reinsurance Corporation, which is at seventh position. The others are much further ahead. All this is happening when India nurses a justifiable ambition to become the reinsurance hub for South Asia.

Insurance rules set by the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (Irdai) mandate that GIC Re has the first right to inspect any risk in the Indian market offered by an insurer. In the insurance business, for big risks, companies do not keep the entire business with themselves but farm it out. The definition of what constitutes a big risk is essentially a business decision. It is usually interpreted as a risk valued at more than 5 per cent of the net worth of the insuring company. This is where the value of reinsurers like GIC Re come in.

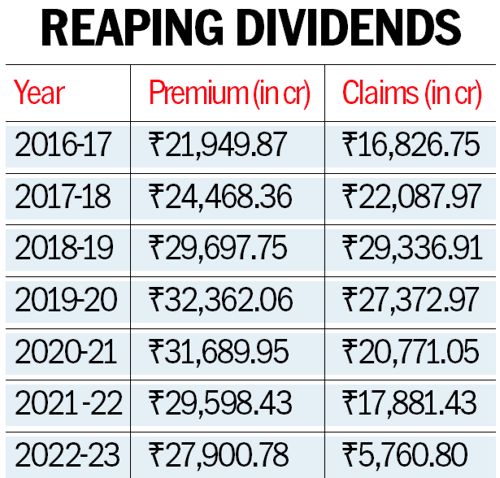

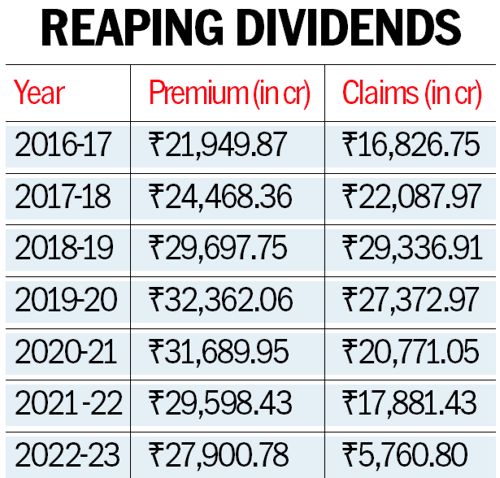

To provide additional comfort to the domestic insurers, Irdai also mandates each of them will offer at least the first 5 per cent of their aggregate reinsurance business to GIC Re — a unique rule in the global insurance industry. This provides the state-owned reinsurer with a steady line of growth. The company’s gross premium written grew over 15 per cent year-on-year in FY20. This is not a happy news, though. It made a loss of Rs 359.10 crore on its underwriting business, a sudden dip from a post-tax profit of Rs 2,224 crore in FY19.

The losses have risen because GIC Re is not big enough to demand the tough underwriting standards from the insurers that foreign reinsurers are demanding from Indian companies in fire and crop insurance. Because it is a government entity, its first line of sight to new risks means it also picks up plenty of unwanted baggage.

One of those is crop insurance. Globally, this is a big and profitable business. But it demands tough underwriting standards by the insuring companies. They, in turn, maintain the standards when the reinsurer cracks the whip. For instance, in assessment of crop losses, the surveys have to be made carefully. In its absence, losses can mount. In India’s agricultural lands, all political parties are keen to demonstrate a high loss but pay insurance at a low premium. Government-run insurance firms such as New India, Oriental or United consequently make massive losses on the business with claims running at an average of over 120 per cent of the premium. When GIC Re swallows this business, its losses also mount.

The implications are clear. The company either refuses to pay for such extravagant losses or eats into its capital. Till recently, before a new management team came on board, it had chosen the latter. In FY20, GIC’s net worth slipped 6.2 per cent in one year. Managing this impossible challenge has costs for a listed entity. The share price of the company dipped from a high of Rs 855 when it was listed in October 2017 to Rs 205.9 on the NSE in April 2021. While specialist insurance ratings agency AM Best had downgraded the Financial Strength Rating (FSR) to B++ (Good) from A- (Excellent), it still does not capture the contradiction in the position of GIC Re. Care Ratings, for instance, has maintained a triple A assessment of the company in the same period.

The good marks to GIC Re’s credit profile from both is based on just one metric — the strength from strong ownership by the government. Left with losses in its primary business, GIC Re covers up with the income it generates from its investments. The company has investments of Rs 28,862.83 crore in government securities as on March 31, 2020, which is about 33 per cent of its total investment portfolio. But remember, insurance investments are supposed to be passive with a horizon of over decades. Filling up for underwriting holes has risks for eventual shareholder returns, not to mention the asset-liability mismatch for infrastructure sector companies to whom it lends.

Of late the company has started to make amends. It has begun to withdraw from the crop insurance coverage of the public sector insurance companies or demand a higher risk premium. It has forced some of the latter to improve their quality control measures. It should do what it has done for fire insurance, increasing the premium it charges for high-risk covers. Covid-19 actually gives it an advantage as more people are willing to be insured, for life, property and business failure risks. Those who are in the lower income deciles will be served even better with a performing reinsurer than with one whose only lifeline is a government bailout. It also encourages GIC Re to grow as the size of the economy warrants.

Source: Business Standard

20-04-2021

20-04-2021

Insurance Alertss

Insurance Alertss